Superior Cluneal Nerve

Anatomy of the radial nerve

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous nerve

Tissue Stretch Decreases Soluble TGF-β1 and Type-1 Procollagen in Mouse Subcutaneous Connective Tissue: Evidence From Ex Vivo and In Vivo Models

Svært interessant studie som viser at å strekke bindevev jevnlig, f.eks. slik vi gjør under behandling eller i yoga, gjør at vi får mindre arrvev. Det produseres mindre TGF-B1, et molekyl som stimulerer arrvevproduksjon. Spesielt for indre organer er dette hjelpsomt, som lunger og tarmer, f.eks. etter operasjoner eller ved betennelsesykdommer. Forskerene viser at det holder å strekke overkroppen så det blir 20-30% lengre avstand mellom hofte og skulder. Dette får vi til med noe så enkelt som å svaie ryggen og strekke armene opp. F.eks. ved å ligge på ryggen over en ball eller gjøre The Founder.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3065715/

We tested the hypothesis that brief (10 min) static tissue stretch attenuates TGF-β1-mediated new collagen deposition in response to injury.

In the in vivo model, microinjury resulted in a significant increase in Type-1 procollagen in the absence of stretch (P < 0.001), but not in the presence of stretch (P = 0.21). Thus, brief tissue stretch attenuated the increase in both soluble TGF-β1 (ex vivo) and Type-1 procollagen (in vivo) following tissue injury. These results have potential relevance to the mechanisms of treatments applying brief mechanical stretch to tissues (e.g., physical therapy, respiratory therapy, mechanical ventilation, massage, yoga, acupuncture).

Transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) is well-established as one of the key cytokines regulating the response of fibroblasts to injury, as well as the pathological production of fibrosis (Barnard et al., 1990;Sporn and Roberts, 1990; Leask and Abraham, 2004). Tissue injury is known to cause auto-induction of TGF-β1 protein production and secretion (Van Obberghen-Schilling et al., 1988; Morgan et al., 2000). Elevated extracellular levels of TGF-β1 have a major impact on extracellular matrix composition by causing autocrine and paracrine activation of fibroblast cell surface receptors, leading to increased synthesis of collagens, elastin, proteoglycans, fibronectin, and tenascin (Balza et al., 1988; Bassols and Massague, 1988; Kahari et al., 1992; Cutroneo, 2003).

In vivo, connective tissue remodeling is not limited to tissue injury, but also occurs in response to changing levels of tissue mechanical forces (e.g., immobilization, beginning a new exercise or occupation). Long-standing physical therapy practices also suggest that externally applied mechanical forces can be used to reduce collagen deposition during tissue repair and scar formation (Cummings and Tillman, 1992).

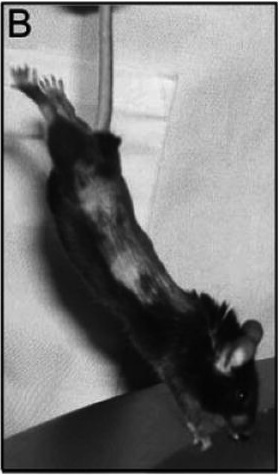

In the stretch group, the mice underwent stretching of the trunk for 10 min twice a day for 7 days in the following manner: each mouse was suspended by the tail such that its paws barely touched a surface slightly inclined relative to the vertical. In response to this maneuver, the mouse spontaneously extended its front and hind limbs (Fig. 1B) with the distance between ipsilateral hip and shoulder joints becoming 20–30% greater than the resting distance.

B: Method used to induce tissue stretch in vivo. Mice are suspended by the tail such that their paws barely touch a surface slightly inclined relative to the vertical. The mice spontaneously extend their front and hind limbs, the distance between ipsilateral hip and shoulder joints becoming 20–30% greater than the resting distance.

Effect of tissue stretch on TGF-β1 protein ex vivo. A: Time course of TGF-β1 protein levels in the culture media for non-stretched (closed circle, N = 4) and stretched (open circle, N = 4) mouse subcutaneous tissue explants on days 0, 1, and 3 post-stretch (or no stretch). All tissue samples were excised and incubated for 24h prior to day 0.B:Levels of TGF-β1 protein in the culture media at day 3 for non-stretched and stretched sbcutaneous tissue samples (N = 36). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from stretched (P = 0.002). Error bars represent standard errors.

Ex vivo tissue injury and cell viability assessment. A: Time course of LDH concentration in the culture media (marker of cell death) for non-stretched (closed circle, n = 4) and stretched (open circle, n = 4) mouse subcutaneous tissue explants on days 0, 1, and 3 post-stretch (or no stretch). B,C: Confocal microscopy imaging of mouse subcutaneous tissue explants showing similar proportions of live (green) and dead (red) cells in non-stretched (A) versus stretched (B) tissue after 3 day incubation post-stretch (or no stretch). Images are projections of three-dimensional image stacks. Scale bars: 40 μm.

Effect of tissue stretch in vivo on subcutaneous tissue Type-1 procollagen in mouse microinjury model. A: Mean ± SE procollagen percent staining area in non-injured versus injured sides, without stretch (N = 11) and with stretch (N = 10); B,C: Type-1 procollagen in non-stretched and stretched tissue (both injured). Scale bars, 40 μm.

First, stretching mouse subcutaneous tissue explants by 20% for 10 min decreases soluble TGF-β1 levels measured 3 days after stretch. During the 4-day incubation, TGF-β1 levels in the culture media increase in both stretched and non-stretched samples; because some tissue trauma occurs at the time of excision, this progressive rise in TGF-β1 is consistent with an injury response. However, the increase in the level of TGF-β1 is slower in the samples that are briefly stretched for 10 min, compared with samples that are not stretched. Since TGF-β1 auto-induction is an important mechanism driving the increase in collagen synthesis following tissue injury (Cutroneo, 2003), we hypothesized that brief stretching of tissue following injury in vivo would decrease soluble TGF-β1 levels, attenuate TGF-β1 auto-induction and decrease new collagen deposition.

Testing this hypothesis in a mouse subcutaneous tissue injury model showed that elongating the tissues of the trunk by 20–30% for 10 min twice a day significantly reduces the amount of subcutaneous new collagen 7 days following subcutaneous tissue injury.

Reducing scar and adhesion formation using stretch and mobilization is especially important for internal tissue injuries and inflammation involving fascia and organs, as opposed to open wounds. For open wounds (including surgical incisions) and severe internal tears (such as a ruptured ligament or tendon), wound closure and strength are critical and thus a certain amount of scarring is necessary and inevitable. In the case of minor sprains and repetitive motion injuries, however, scarring is mostly detrimental since it can contribute to maintaining the chronicity of tissue stiffness, abnormal movement patterns, and pain (Langevin and Sherman, 2007).

We have proposed that therapies that briefly stretch tissues beyond the habitual range of motion (physical therapy, massage, yoga, acupuncture) locally inhibit new collagen formation for several days after stretch and thus prevent and/or ameliorate soft tissue adhesions (Langevin et al., 2001, 2002, 2005, 2006a, 2007).

Proposed model for healing of connective tissue injury in the absence (A,C,E) and presence (B,D,F) of tissue stretch. In this model, brief stretching of tissue beyond the habitual range of motion reduces soluble TGF-β1 levels (D) causing a decrease in the fibrotic response, less collagen deposition, and reduced tissue adhesion (F) compared with no stretch (E). Black lines represent newly formed collagen.

Structure of the rat subcutaneous connective tissue in relation to its sliding mechanism.

Om hvordan bindevevet i huden beveger seg når man strekker huden. Nevner at nerver og blodårer har veldig svingete baner i huden, og at dette gjør at vi tåler mye strekk og bevegelse uten at disse strekkes eller ødelegges.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14527168/

The subcutaneous connective tissue was observed to be composed of multiple layers of thin collagen sheets containing elastic fibers. These piled-up collagen sheets were loosely interconnected with each other, while the outer and inner sheets were respectively anchored to the dermis and epimysium by elastic fibers. Collagen fibers in each sheet were variable in diameter and oriented in different directions to form a thin, loose meshwork under conditions without mechanical stretching.

When a weak shear force was loaded between the skin and the underlying abdominal muscles, each collagen sheet slid considerably, resulting in a stretching of the elastic fibers which anchor these sheets. When a further shear force was loaded, collagen fibers in each sheet seemed to align in a more parallel manner to the direction of the tension. With the reduction or removal of the force, the arrangement of collagen fibers in each sheet was reversed and the collagen sheets returned to their original shapes and positions, probably with the stabilizing effect of elastic fibers.

Blood vessels and nerves in the subcutaneous connective tissue ran in tortuous routes in planes parallel to the unloaded skin, which seemed very adaptable for the movement of collagen sheets. These findings indicate that the subcutaneous connective tissue is extensively mobile due to the presence of multilayered collagen sheets which are maintained by elastic fibers.

Immunohistochemical analysis of wrist ligament innervation in relation to their structural composition.

Nevner at noen ligamenter i håndleddethar mye innervasjon og er viktige for propriosepsjon, mens andre har ikke det. Sier at innervasjonen sitter helt ytterst i ligamentene. Nevner at det meste av innerverte ligamenter er på oversiden.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17218173/

The innervation pattern in the ligaments was found to vary distinctly, with a pronounced innervation in the dorsal wrist ligaments (dorsal radiocarpal, dorsal intercarpal, scaphotriquetral, dorsal scapholunate interosseous), an intermediate innervation in the volar triquetral ligaments (palmar lunotriquetral interosseous, triquetrocapitate, triquetrohamate), and only limited/occasional innervation in the remaining volar wrist ligaments. The innervation pattern also was reflected in the structural differences between the ligaments.

When present, mechanoreceptors and nerve fibers were consistently found in the loose connective tissue in the outer region (epifascicular region) of the ligament. Hence, ligaments with abundant innervation had a large epifascicular region, as compared with the ligaments with limited innervation, which consisted mostly of densely packed collagen fibers.

The results of our study suggest that wrist ligaments vary with regard to sensory and biomechanical functions. Rather, based on the differences found in structural composition and innervation, wrist ligaments are regarded as either mechanically important ligaments or sensory important ligaments. The mechanically important ligaments are ligaments with densely packed collagen bundles and limited innervation. They are located primarily in the radial, force-bearing column of the wrist. The sensory important ligaments, by contrast, are richly innervated although less dense in connective tissue composition and are related to the triquetrum. The triquetrum and its ligamentous attachments are regarded as key elements in the generation of the proprioceptive information necessary for adequate neuromuscular wrist stabilization.

The fascia of the limbs and back – a review

Never det meste rundt bindevev: tensegritet, subcutan hud, skinligaments, stretching, ligamenter, nerver, m.m.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2667913/

Fasciae probably hold many of the keys for understanding muscle action and musculoskeletal pain, and maybe of pivotal importance in understanding the basis of acupuncture and a wide range of alternative therapies (Langevin et al. 2001, 2002, 2006a; Langevin & Yandow, 2002; Iatridis et al. 2003). Intriguingly, Langevin et al. (2007) have shown that subtle differences in the way that acupuncture needles are manipulated can change how the cells in fascia respond. The continuum of connective tissue throughout the body, the mechanical role of fascia and the ability of fibroblasts to communicate with each other via gap junctions, mean that fascia is likely to serve as a body-wide mechanosensitive signaling system with an integrating function analogous to that of the nervous system (Langevin et al. 2004; Langevin, 2006). It is indeed a key component of a tensegrity system that operates at various levels throughout the body and which has been considered in detail by Lindsay (2008) in the context of fascia.

Anatomists have long distinguished between superficial and deep fascia (Fig. 1), although to many surgeons, ‘fascia’ is simply ‘deep fascia’. The superficial fascia is traditionally regarded as a layer of areolar connective or adipose tissue immediately beneath the skin, whereas deep fascia is a tougher, dense connective tissue continuous with it.

A diagrammatic representation of a transverse section through the upper part of the leg showing the relative positions of the superficial (SF) and deep fascia (DF) in relation to the skin (S) and muscles. Note how the deep fascia, in association with the bones [tibia (T) and fibula (F)] and intermuscular septa (IS) forms a series of osteofascial compartments housing the extensor, peroneal (PER) and flexor muscles. If pressure builds up within a compartment because of an acute or overuse injury, then the vascular supply to the muscles within it can be compromised and ischaemia results. ANT, anterior compartment; IM, interosseous membrane.

The presence of a significant layer of fat in the superficial fascia is a distinctive human trait (thepanniculus adiposus), compensating for the paucity of body hair. It thus plays an important role in heat insulation. In hairy mammals, the same fascia is typically an areolar tissue that allows the skin to be readily stripped from the underlying tissues (Le Gros Clark, 1945). Where fat is prominent in the superficial fascia (as in man), it may be organized into distinctive layers, or laminae (Johnston & Whillis, 1950), although Gardner et al. (1960) caution that these may sometimes be a characteristic of embalmed cadavers and not evident in the living person. Furthermore, Le Gros Clark (1945) also argues that fascial planes can be artefactually created by dissection. Conversely, however, some layers of deep fascia are more easily defined in fresh than in fixed cadavers (Lytle, 1979).

The superficial fascia conveys blood vessels and nerves to and from the skin and often promotes movement between the integument and underlying structures.

Skin mobility protects both the integument and the structures deep to it from physical damage. Mobility is promoted by multiple sheets of collagen fibres coupled with the presence of elastin (Kawamata et al. 2003). The relative independence of the collagen sheets from each other promotes skin sliding and further stretching is afforded by a re-alignment of collagen fibres within the lamellae. The skin is brought back to its original shape and position by elastic recoil when the deforming forces are removed. As Kawamata et al. (2003)point out, one of the consequences of the movement-promoting characteristics of the superficial fascia is that the blood vessels and nerves within it must run a tortuous route so that they can adapt to an altered position of the skin, relative to the deeper structures.

Although deep fascia elsewhere in the limbs is often not so tightly bound to the skin, nevertheless cutaneous ligaments extending from deep fascia to anchor the integument are much more widespread than generally recognized and serve to resist a wide variety of forces, including gravitational influences (Nash et al. 2004).

According to Bouffard et al. (2008), brief stretching decreases TGF-β1-mediated fibrillogenesis, which may be pertinent to the deployment of manual therapy techniques for reducing the risk of scarring/fibrosis after an injury. As Langevin et al. (2005) point out, such striking cell responses to mechanical load suggest changes in cell signaling, gene expression and cell-matrix adhesion.

In contrast, Schleip et al. (2007) have reported myofibroblasts in the rat lumbar fascia (a dense connective tissue). The cells can contract in vitro andSchleip et al. (2007) speculate that similar contractions in vivo may be strong enough to influence lower back mechanics. Although this is an intriguing suggestion that is worthy of further exploration, it should be noted that tendon cells immunolabel just as strongly for actin stress fibres as do fascial cells and this may be associated with tendon recovery from passive stretch (Ralphs et al. 2002). Finally, the reader should also note that true muscle fibres (both smooth and skeletal) can sometimes be found in fascia. Smooth muscle fibres form the dartos muscle in the superficial fascia of the scrotum and skeletal muscle fibres form the muscles of fascial expression in the superficial fascia of the head and neck.

Consequently, entheses are designed to reduce this stress concentration, and the anatomical adaptations for so doing are evident at the gross, histological and molecular levels. Thus many tendons and ligaments flare out at their attachment site to gain a wide grip on the bone and commonly have fascial expansions linking them with neighbouring structures. Perhaps the best known of these is the bicipital aponeurosis that extends from the tendon of the short head of biceps brachii to encircle the forearm flexor muscles and blend with the antebrachial deep fascia (Fig. 6). Eames et al. (2007) have suggested that this aponeurosis may stabilize the tendon of biceps brachii distally. In doing so, it reduces movement near the enthesis and thus stress concentration at that site.

The bicipital aponeurosis (BA) is a classic example of a fascial expansion which arises from a tendon (T) and dissipates some of the load away from its enthesis (E). It originates from that part of the tendon associated with the short head of biceps brachii (SHB) and blends with the deep fascia (DF) covering the muscles of the forearm. The presence of such an expansion at one end of the muscle only, means that the force transmitted through the proximal and distal tendons cannot be equal. LHB, long head of biceps brachii. Photograph courtesy of S. Milz and E. Kaiser.

Several reports suggest that fascia is richly innervated, and abundant free and encapsulated nerve endings (including Ruffini and Pacinian corpuscles) have been described at a number of sites, including the thoracolumbar fascia, the bicipital aponeurosis and various retinacula (Stilwell, 1957; Tanaka & Ito, 1977; Palmieri et al. 1986; Yahia et al. 1992; Sanchis-Alfonso & Rosello-Sastre, 2000; Stecco et al. 2007a).

Changes in innervation can occur pathologically in fascia, and Sanchis-Alfonso & Rosello-Sastre (2000) report the ingrowth of nociceptive fibres, immunoreactive to substance P, into the lateral knee retinaculum of patients with patello-femoral malignment problems.

Stecco et al. (2008) argue that the innervation of deep fascia should be considered in relation to its association with muscle. They point out, as others have as well (see below in ‘Functions of fascia’) that many muscles transfer their pull to fascial expansions as well as to tendons. By such means, parts of a particular fascia may be tensioned selectively so that a specific pattern of proprioceptors is activated.

It is worth noting therefore that Hagert et al. (2007) distinguish between ligaments at the wrist that are mechanically important yet poorly innervated, and ligaments with a key role in sensory perception that are richly innervated. There is a corresponding histological difference, with the sensory ligaments having more conspicuous loose connective tissue in their outer regions (in which the nerves are located). Comparable studies are not available for deep fascia, although Stecco et al. (2007a) report that the bicipital aponeurosis and the tendinous expansion of pectoralis major are both less heavily innervated than the fascia with which they fuse. Where nerves are abundant in ligaments, blood vessels are also prominent (Hagert et al. 2005). One would anticipate similar findings in deep fascia.

Some of the nerve fibres associated with fascia are adrenergic and likely to be involved in controlling local blood flow, but others may have a proprioceptive role. Curiously, however, Bednar et al. (1995)failed to find any nerve fibres in thoracolumbar fascia taken at surgery from patients with low back pain.

The unyielding character of the deep fascia enables it to serve as a means of containing and separating groups of muscles into relatively well-defined spaces called ‘compartments’.

One of the most influential anatomists of the 20th century, Professor Frederic Wood Jones, coined the term ‘ectoskeleton’ to capture the idea that fascia could serve as a significant site of muscle attachment – a ‘soft tissue skeleton’ complementing that created by the bones themselves (Wood Jones, 1944). It is clearly related to the modern-day concept of ‘myofascia’ that is popular with manual therapists and to the idea of myofascial force transmission within skeletal muscle, i.e. the view that force generated by skeletal muscle fibres is transmitted not only directly to the tendon, but also to connective tissue elements inside and outside the skeletal muscle itself (Huijing et al. 1998; Huijing, 1999).

One can even extend this idea to embrace the concept that agonists and antagonists are mechanically coupled via fascia (Huijing, 2007). Thus Huijing (2007) argues that forces generated within a prime mover may be exerted at the tendon of an antagonistic muscle and indeed that myofascial force transmission can occur between all muscles of a particular limb segment.

Wood Jones (1944) was particularly intrigued by the ectoskeletal function of fascia in the lower limb. He related this to man’s upright stance and thus to the importance of certain muscles gaining a generalized attachment to the lower limb when it is viewed as a whole weight-supporting column, rather than a series of levers promoting movement. He singled out gluteus maximus and tensor fascia latae as examples of muscles that attach predominantly to deep fascia rather than bone (Wood Jones, 1944).

They have argued that a common attachment to the thoracolumbar fascia means that the latter has an important role in integrating load transfer between different regions. In particular, Vleeming et al. (1995) have proposed that gluteus maximus and latissimus dorsi (two of the largest muscles of the body) contribute to co-ordinating the contralateral pendulum like motions of the upper and lower limbs that characterize running or swimming. They suggest that the muscles do so because of a shared attachment to the posterior layer of the thoracolumbar fascia. Others, too, have been attracted by the concept of muscle-integrating properties of fascia. Thus Barker et al. (2007) have argued for a mechanical link between transversus abdominis and movement in the segmental neutral zone of the back, via the thoracolumbar fascia. They feel that the existence of such fascial links gives an anatomical/biomechanical foundation to the practice in manual therapy of recommending exercises that provoke a submaximal contraction of transversus abdominis in the treatment of certain forms of low back pain.

An important function of deep fascia in the limbs is to act as a restraining envelope for muscles lying deep to them. When these muscles contract against a tough, thick and resistant fascia, the thin-walled veins and lymphatics within the muscles are squeezed and their unidirectional valves ensure that blood and lymph are directed towards the heart. Wood Jones (1944) contests that the importance of muscle pumping for venous and lymphatic return is one of the reasons why the deep fascia in the lower limb is generally more prominent than in the upper – because of the distance of the leg and foot below the heart.

In certain regions of the body, fascia has a protective function. Thus, the bicipital aponeurosis (lacertus fibrosus), a fascial expansion arising from the tendon of the short head of biceps brachii (Athwal et al. 2007), protects the underlying vessels. It also has mechanical influences on force transmission and stabilizes the tendon itself distally (Eames et al. 2007).

Immunohistochemical demonstration of nerve endings in iliolumbar ligament.

Ett par studier som bekrefter at IL ligamentet er fullt av nervetråder. Viktig å vite for ligamentbehandlingen vi gjør på Verkstedet.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20081564

The function of iliolumbar ligament and its role in low back pain has not been yet fully clarified. Understanding the innervation of this ligament should provide a ground which enables formation of stronger hypotheses.

Iliac wing insertion was found to be the richest region of the ligament in terms of mechanoreceptors and nociceptors. Pacinian (type II) mechanoreceptor was determined to be the most common (66.67%) receptor followed by Ruffini (type I) (19.67%) mechanoreceptor, whereas free nerve endings (type IV) and Golgi tendon organs (type III) were found to be less common, 10.83% and 2.83%, respectively.

Those results indicate that ILL plays an important role in proprioceptive coordination of lumbosacral region alongside its known biomechanic support function. Moreover, the presence of type IV nerve endings suggest that the injury of this ligament might contribute to the low back pain.

Mer om IL ligamentet i denne studien:

Robert Schleip – Curiouser and curiouser

Robert Schleips foredrag om nye innsikter i hva som skjer i bindevevet under Rolfing. Fra 2012.