Omfattende studie som beskriver hvordan vi har tilpasset oss høyere nivåer av oksygen. Bekrefter alle innspill jeg har hatt om oksygen sin destruktive effekt og at beskyttelsen mot oksygenets skadevirkninger er viktigere enn å få mer oksygen inn i kroppen. Lunger, sirkulasjonssystem, hemoglobin, antioksidantsystem og det at mitokondriene er godt gjemt inni en annen celle som er godt beskyttet av en tett cellevegg er forsvars- og reguleringsmekanismer mot det livsfarlige men også livsnødvendige oksygenet.

Nevner at den opprinnelige atmosfæren bestod av veldig lite O2(1-2% eller 2,4 mmHg) og mer enn dobbelt så mye CO2. Dette er miljøet mitokondriene ble utviklet i for 2,7 billioner år siden, og som de fortsatt lever i inni cellene våre. Om oksygennivået økes tilmer enn dette blir mitokondriene dårligere og mister sin funksjon.

Nevner også at forsvarsmekanismene mot oksygen var tilstede helt fra starten. Og hemoglobin (blodcelle i dyr) og klorofyll (i planter) tilfredstiller alle de nødvendige beskyttende egenskapene vi trenger mot oksygen.

Nevner at CO2 var den første antioksidanten i evolusjonen.

Beskriver også det som skjer i mitokondria, at hypoxi (lavere O2 tilgjengelighet) gir mindre ROS og økt mitochondrial uncoupling (produksjon av varme istedet for ATP). Vi kan se dette som om mitokondriene går på tomgang med lavt turtall, mens ATP produksjon er høyt turtall og dermed også mer slitasje.

Nevner også evolusjonen av diafragma som den primære pustemuskelen.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3926130/

Abstract

Life originated in anoxia, but many organisms came to depend upon oxygen for survival, independently evolving diverse respiratory systems for acquiring oxygen from the environment. Ambient oxygen tension (PO2) fluctuated through the ages in correlation with biodiversity and body size, enabling organisms to migrate from water to land and air and sometimes in the opposite direction. Habitat expansion compels the use of different gas exchangers, for example, skin, gills, tracheae, lungs, and their intermediate stages, that may coexist within the same species; coexistence may be temporally disjunct (e.g., larval gills vs. adult lungs) or simultaneous (e.g., skin, gills, and lungs in some salamanders). Disparate systems exhibit similar directions of adaptation: toward larger diffusion interfaces, thinner barriers, finer dynamic regulation, and reduced cost of breathing. Efficient respiratory gas exchange, coupled to downstream convective and diffusive resistances, comprise the “oxygen cascade”—step-down of PO2 that balances supply against toxicity. Here, we review the origin of oxygen homeostasis, a primal selection factor for all respiratory systems, which in turn function as gatekeepers of the cascade. Within an organism’s lifespan, the respiratory apparatus adapts in various ways to upregulate oxygen uptake in hypoxia and restrict uptake in hyperoxia. In an evolutionary context, certain species also become adapted to environmental conditions or habitual organismic demands. We, therefore, survey the comparative anatomy and physiology of respiratory systems from invertebrates to vertebrates, water to air breathers, and terrestrial to aerial inhabitants. Through the evolutionary directions and variety of gas exchangers, their shared features and individual compromises may be appreciated.

Introduction

Oxygen, a vital gas and a lethal toxin, represents a trade-off with which all organisms have had a conflicted relationship. While aerobic respiration is essential for efficient metabolic energy production, a prerequisite for complex organisms, cumulative cellular oxygen stress has also made senescence and death inevitable. Harnessing the energy from oxidative phosphorylation while minimizing cellular stress and damage is an eternal struggle transcending specific organ systems or species, a conflict that shaped an assortment of gas-exchange systems.

The respiratory organ is the “gatekeeper” that determines the amount of oxygen available for distribution. Gas exchangers arose as simple air-blood diffusion interfaces that in active animals progressively gained in complexity in coordination with the cardiovascular system, leading to serial “step-downs” of oxygen tension to maintain homeostasis between uptake distribution and cellular protection.

While a comprehensive treatment of the evolutionary physiology of respiration is beyond the scope of any one article, here we focuses on the first step of the oxygen cascade—convection and diffusion in the gas-exchange organ—to provide an overview of the diversity of nature’s “solutions” to the dilemma of acquiring enough but not too much oxygen from the environment.

Ubiquity of Reactive Oxygen Species

As reviewed by Lane (407) and Maina (466), the primary atmosphere contained mainly nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and water vapor. Much of these were swept away by meteorite bombardment and replaced with a secondary atmosphere (416-418, 579, 590) consisting of hydrogen sulfide, cyanide, carbon monoxide, carbon doxide, methane, and more water vapor from volcanic eruptions. Only trace oxygen (<0.01% present atmospheric level) existed (418), originated from inorganic (photolysis and peroxy hydrolysis) (622) and organic (photosynthesis) sources.

Oxidative respiration is the reverse process as O2 accepts four electrons successively to form water. Many of these steps are catalyzed by transitional metal ions (e.g., iron, copper, and magnesium). Therefore, aerobic respiration, oxygen toxicity and radiation poisoning represent equivalent forms of oxidative stress (407).

Origin of Oxygen Sensing and Antioxidation—Metalloproteins

If oxidative stress was present from the beginning, early anaerobic organisms must have possessed effective antioxidant defenses, including mechanism(s) for controlled O2 sensing, storage, transport, and release as well as pathways for neutralizing ROS. The general class of compounds that fulfill these requirements is the metalloproteins that transfer electrons via transitional metals (766, 767), for example, heme proteins and chlorophyll (Fig. 2).

Hydrogen may have been the first electron donor and CO2 the first electron acceptor for synthesizing ATP by chemiosmosis (408).

Because of a high redox potential of O2 as the terminal electron acceptor in electron transport, aerobic respiration is far more efficient in energy production (36 moles of ATP per mole of glucose) than anaerobic respiration (~5 moles). Aerobic multicellular organisms arose approximately 1 Ga and more complex organisms such as marine molluscs thrived approximately 550 to 500 million years ago (Ma). Exposed to a still low O2 tension in the deep sea, these organisms uniformly possessed metalloprotein respiratory pigments with a characteristically high O2 affinity for efficient O2 storage and slow O2 release thereby avoiding flooding the cell with excessive ROS (783). Contemporary myoglobin continues to perform this regulatory function in muscle.

It is well recognized that embryos and undifferentiated cells grow better in a hypoxia (129, 153). A low O2 tension (1%-5%) is an important component of the embryonic and mesenchymal stem cell “niche” that maintains stem cell properties, minimizes oxidative stress, prevents chromosomal abnormalities, improves clonal survival, and perpetuates the undifferentiated characteristics (457). In addition, hypoxia stimulates endothelial cell proliferation, migration, tubulogenesis, and stress resistance (752, 850) as well as preferential growth and vascularization of many malignant tumor cells; the latter observation constitutes the basis for the use of adjuvant hyperoxia to enhance tumor killing during irradiation and chemotherapy (277,738). Collectively, these responses to O2 tension suggest that the pulmonary gas-exchange organs adapted in a direction toward controlled restriction of cellular exposure to O2.

Origin of the Oxygen Cascade

The oxygen cascade (Fig. 6) describes serial step-downs of O2 tension from ambient air through successive resistances across the pulmonary, cardiac, macrovascular and microvascular systems into the cell and mitochondria. These resistances adapt in a coordinated fashion in response to changes in ambient O2 availability or utilization (333). Traditional paradigm holds that the primary selection pressure in the evolution of O2 transport systems is the efficiency of O2 delivery to meet cellular metabolic demands. If this is the sole function of the cascade, why are there so many resistances? Once we accept the anaerobic origin of eukaryotes and their persistent preference for hypoxia, an alternative paradigm becomes plausible, namely, the entire oxygen cascade could be viewed as an elaborate gate-keeping mechanism the major function of which is to balance cellular O2 delivery against oxidative damage.

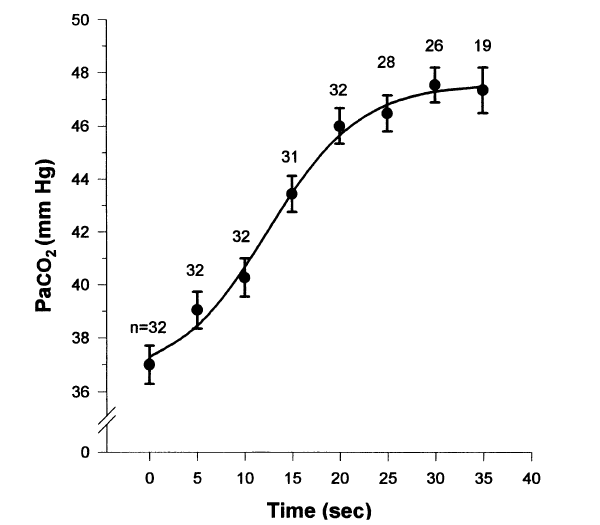

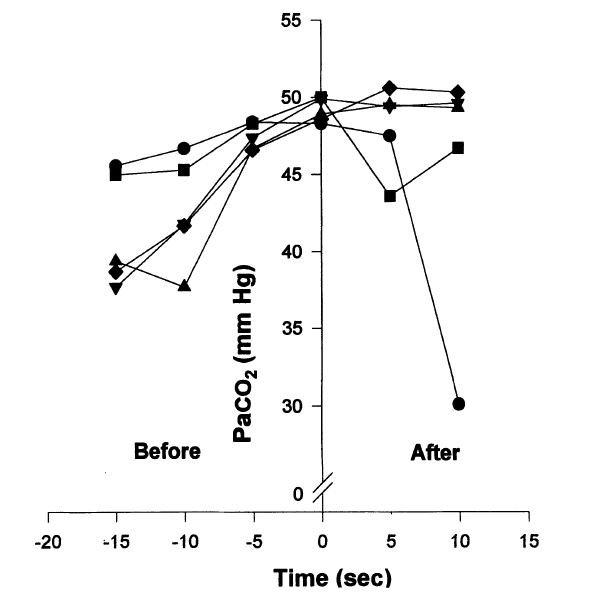

Mitochondria consume the majority of cellular O2, directly control intracellular O2 tension, and generate most of the cellular ROS (136). Intracellular O2 tension in turn regulates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, ROS production, cell signaling, and gene expression. Via O2-dependent oxidative phosphorylation the mitochondria act as cellular O2 sensors in the regulation of diverse responses from local blood flow to electric activity (830). Earlier studies reported that hypoxia increases mitochondrial ROS generation (126, 782, 823) via several mechanisms: (i) O2 limitation at the terminal complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) in the mitochondrial electron transport chain causes electrons to back up the chain with increased electron leak to form superoxide (•O2−). (ii) Hypoxia induces conformational changes in complex III (ubiquinol cytochrome c oxidoreductase) to enhance superoxide formation (88, 287). (iii) Oxidized cytochrome c scavenges superoxide (722). Hypoxia-induced O2 limitation at complex IV leads to cytochrome c reduction, limiting its ability to scavenge superoxide and enhancing mitochondrial ROS leakage. However, recent studies of isolated mitochondria show that hypoxia actually reduces mitochondrial ROS generation and causes mitochondrial uncoupling, suggesting extramitochondrial sources of ROS generation in hypoxia (330). These conflicting reports remain to be resolved. Nonetheless, moderate hypoxia rapidly and reversibly downregulates mitochondrial enzyme transcripts, in parallel with reductions in mitochondrial respiratory activity and O2 consumption (631).

As paleo-atmospheric O2 concentration increased and multicellular aerobic organisms arose, the endosymbiotic mitochondria-host relationship faced the challenge of balancing conflicting needs of aerobic energy generation for the host cell and anaerobic protection for its internal power generator. The host cell must finely control a constant supply of O2 to the mitochondria for oxidative phosphorylation while simultaneously protecting mitochondria against oxidative damage by maintaining a near-anoxic level of local O2 concentration. This trade-off may have led to the evolution of ever more elaborate physicochemical barriers that created and maintained successive O2 partial pressure gradients, by convection and diffusion in the lung, chemical binding to hemoglobin, distribution and release via cardiovascular delivery, dissociation from hemoglobin, and diffusion into peripheral cells with or without myoglobin facilitated transport. As a result, the primordial anoxic conditions of the Earth necessary for survival and optimal function of this proteobacterial remnant are preserved inside the host cell. In working human leg muscle O2 tension at the sarcoplasmic and mitochondrial boundaries has been estimated at approximately 2.4 mmHg (0.32 kPa) (835) and muscle mitochondrial O2 concentration at half-maximal metabolic rate 0.02 to 0.2 mmHg (834), that is, in the range of the ancient atmospheric level approximately 2 Ga. Raising O2 tension above these levels impairs mitochondrial activity (672). In this context, protection of mitochondria from O2 exposure likely constitutes a major selection factor in the evolution of complex aerobic life while the various forms of systemic O2 delivery systems are necessary but secondary functions that sustain the “gate-keeping” barrier apparatus to maintain adequate partial pressure gradients along the O2 transport cascade and preserve the near-anoxic intracellular conditions for the mitochondria. In parallel with physical barriers, cells also developed various biochemical scavenging and antioxidant pathways to counteract the toxic effects of ROS as ambient oxygenation increased.

Defense against the Dark Arts of Oxidation

To summarize, the evolution of life on Earth has adapted to a wide range of ambient O2 levels from 0% to 35%. Periods of relative hyperoxia promote biodiversity and gigantism but incur excess oxidative stress and mandating the upregulation of antioxidant defenses. Periods of relative hypoxia promote coordinated conservation of resources and downregulation of metabolic capacities to improve energy efficiency and channel some savings into compensatory growth of gas-exchange organs. The trajectory of early evolution is at least partly coupled to O2 content of the atmosphere and the deep ocean, and there is a plausible explanation for the coupling, namely, defense against the dark arts of oxidation. Oxygen is capable of giving and taking life. The anaerobic proteobacteria escaped the fate of annihilation by taking refuge inside another cell and in a brilliant evolutionary move coopted its own oxygen-detoxifying machinery to provide essential sustenance for the host cell in return for nourishment and physical protection from oxidation. As the threat of oxidation increased with rising environmental O2 concentration, selection pressure escalated for ever more sophisticated defense mechanisms against oxidative injury and in direct conflict with simultaneously escalating selection pressures to harness the energetic advantage of oxidative phosphorylation.

Trading off the above opposing demands shaped all known respiratory organs, from simple O2 diffusion across cell membranes to facilitated transport via O2 binding proteins to gas-exchange systems of varying complexity (skin, gills, tracheae, book lung, alveolar lung, and avian lung) (Sections 2-5). Concurrently evolving with a convective transport system, these increasingly elaborate respiratory organs not only increase O2 uptake but also maintain air-to-mitochondria O2 tension gradients and intracellular O2 fluxes at a hospitable ancestral level. This epic struggle began at the dawn of life and persisted to the present on a universal scale. The evolutionary trajectory of air breathing has continued contemporary significance to the understanding of oxygen-dependent metabolic homeostasis, especially in relation to maturation, senescence, and aging-related organ degeneration and disease.