Om CO2 i helbredelse av vev. Viktig oversikt som nevner CO2 sin bane og effekt gjennom hele organismen – fra DNA til celle til vev til blod. Bekrefter ALT jeg har funnet om CO2 og pusteknikkene. Nevner også potensiell farer, som kun skjer ved akutt hypercapnia. Nevner også en meget spennende konsept om å buffre CO2 acidose med bikarbonat (Natron). I kliniske tilfeller på sykehus kan det ha negative effekter, men hos normale mennesker vil det virke som en effektiv buffer.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2887152/

Hypercapnia may play a beneficial role in the pathogenesis of inflammation and tissue injury, but may hinder the host response to sepsis and reduce repair. In contrast, hypocapnia may be a pathogenic entity in the setting of critical illness.

For practical purposes, PaCO2 reflects the rate of CO2 elimination.

The commonest reason for hypercapnia in ventilated patients is a reduced tidal volume (VT); this situation is termed permissive hypercapnia.

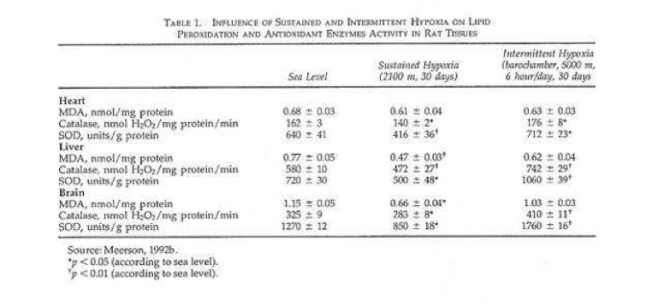

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2887152/table/T1/?report=previmg

High VT causes, or potentiates, lung injury [4]. Smaller VT often leads to elevated PaCO2, termed permissive hypercapnia, and is associated with better survival [5,6]. These low-VT strategies are not confined to patients with acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS); they were first reported successful in severe asthma [7], and attest to the overall safety of hypercapnia. Indeed, hypercapnia in the presence of higher VT may independently improve survival [8].

Hypocapnia is common in several diseases (Table (Table1;1; for example, early asthma, high-altitude pulmonary edema, lung injury), is a common acid-base disturbance and a criterion for systemic inflammatory response syndrome [9], and is a prognostic marker of adverse outcome in diabetic ketoacidosis [10]. Hypocapnia – often prolonged – remains common in the management of adult [11] and pediatric [12] acute brain injury.

Table 1

Causes of hypocapnia

| Hypoxemia | Altitude, pulmonary disease |

| Pulmonary disorders | Pneumonia, interstitial pneumonitis, fibrosis, edema, pulmonary emboli, vascular disease, bronchial asthma, pneumothorax |

| Cardiovascular system disorders | Congestive heart failure, hypotension |

| Metabolic disorders | Acidosis (diabetic, renal, lactic), hepatic failure |

| Central nervous system disorders | Psychogenic/anxiety hyperventilation, central nervous system infection, central nervous system tumors |

| Drug induced | Salicylates, methylxanthines, β-adrenergic agonists, progesterone |

| Miscellaneous | Fever, sepsis, pain, pregnancy |

CO2 is carried in the blood as HCO3-, in combination with hemoglobin and plasma proteins, and in solution. Inside the cell, CO2 interacts with H2O to produce carbonic acid (H2CO3), which is in equilibrium with H+ and HCO3-, a reaction catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase. CO2 transport into cells is complex, and passive diffusion, specific transporters and rhesus proteins may all be involved.

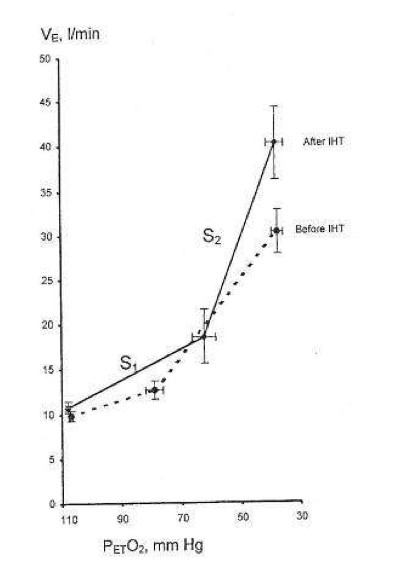

CO2 is sensed in central and peripheral neurons. Changes in CO2 and H+ are sensed in chemosensitive neurons in the carotid body and in the hindbrain [13,14]. Whether CO2 or the pH are preferentially sensed is unclear, but the ventilatory response to hypercapnic acidosis (HCA) exceeds that of an equivalent degree of metabolic acidosis [15], suggesting specific CO2 sensing.

An in vitro study has demonstrated that elevated CO2 levels suppress expression of TNF and other cytokines by pulmonary artery endothelial cells via suppression of NF-κB activation [18].

Furthermore, hypercapnia inhibits pulmonary epithelial wound repair also via an NF-κB mechanism [19].

The physiologic effects of CO2 are diverse and incompletely understood, with direct effects often counterbalanced by indirect effects.

Hypocapnia can worsen ventilation-perfusion matching and gas exchange in the lung via a number of mechanisms, including bronchoconstriction [21], reduction in collateral ventilation [22], reduction in parenchymal compliance [23], and attenuation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and increased intrapulmonary shunting [24].

CO2 stimulates ventilation (see above). Peripheral chemoreceptors respond more rapidly than the central neurons, but central chemosensors make a larger contribution to stimulating ventilation. CO2increases cerebral blood flow (CBF) by 1 to 2 ml/100 g/minute per 1 mmHg in PaCO2[25], an effect mediated by pH rather than by the partial pressure of CO2.

Hypercapnia elevates both the partial pressure of O2 in the blood and CBF, and reducing PaCO2 to 20 to 25 mmHg decreases CBF by 40 to 50% [26]. The effect of CO2 on CBF is far larger than its effect on the cerebral blood volume. During sustained hypocapnia, CBF recovers to within 10% baseline by 4 hours; and because lowered HCO3-returns the pH towards normal, abrupt normalization of CO2 results in (net) alkalemia and risks rebound hyperemia.

Hypocapnia increases both neuronal excitability and excitatory (glutamatergic) synaptic transmission, and suppresses GABA-A-mediated inhibition, resulting in increased O2 consumption and uncoupling of metabolism to CBF [27].

Hypercapnia directly inhibits cardiac and vascular muscle contractility, effects that are counterbalanced by sympathoadrenal increases in heart rate and contractility, increasing the cardiac output overall [28].

Indeed, a large body of evidence now attests to the ability of hypercapnia to increase peripheral tissue oxygenation, independently of its effects on cardiac output [30,31].

The beneficial effects of HCA in such models are increasingly well understood, and include attenuation of lung neutrophil recruitment, pulmonary and systemic cytokine concentrations, cell apoptosis, and O2-derived and nitrogen-derived free radical injury.

Concern has been raised regarding the potential for the anti-inflammatory effects of HCA to impair the host response to infection. In early pulmonary infection, this potential impairment does not appear to occur, with HCA reducing the severity of acute-severe Escherichia coli pneumonia-induced ALI [41]. In the setting of more established E. coli pneumonia, HCA is also protective [42].

Hypocapnia increases microvascular permeability and impairs alveolar fluid reabsorption in the isolated rat lung, due to an associated decrease in Na/K-ATPase activity [47].

HCA protects the heart following ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Hypercapnia attenuates hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in the immature rat [52] and protects the porcine brain from reoxygenation injury by attenuation of free radical action. Hypercapnia increases the size of the region at risk of infarction in experimental acute focal ischemia; in hypoxic-ischemic injury in the immature rat brain, hypocapnia worsens the histologic magnitude of stroke [52] and is associated with a decrease in CBF to the hypoxia-injured brain as well as disturbance of glucose utilization and phosphate reserves.

Indeed, hypocapnia may be directly neurotoxic, through increased incorporation of choline into membrane phospholipids [56].

Rapid induction of hypercapnia in the critically ill patient may have adverse effects. Acute hypercapnia impairs myocardial function.

In patients managed with protective ventilation strategies, buffering of the acidosis induced by hypercapnia remains a common – albeit controversial – clinical practice.

While bicarbonate may correct the arterial pH, it may worsen an intracellular acidosis because the CO2 produced when bicarbonate reacts with metabolic acids diffuses readily across cell membranes, whereas bicarbonate cannot.

Hypocapnia is an underappreciated phenomenon in the critically ill patient, and is potentially deleterious, particularly when severe or prolonged. Hypocapnia should be avoided except in specific clinical situations; when induced, hypercapnic acidosis should be for specific indications while definitive measures are undertaken.

relative to pulmonary O2 uptake (

relative to pulmonary O2 uptake ( ) can be used to quantify θL validly if aerobic and hyperventilatory sources can be ruled out, i.e. θL is then attributable to the decrease in muscle and blood [HCO3−

) can be used to quantify θL validly if aerobic and hyperventilatory sources can be ruled out, i.e. θL is then attributable to the decrease in muscle and blood [HCO3−