Svært viktig review om IHT – intermittend hypoxia training – som det har blitt gjort mye forskning på i russland, men først nå begynt å bli interessant i vesten. Nevner hvordan co2 reageer på hypoxi, og nervesystemet og vevet og i mitchondria, inklidert at SOD øker med 70% og at IHT normaliserer NO som lagres i blodkarene. Om at IHT kan brukes i behandling av sykdommer, inkludert strålingskader fra Chernobyl. Metoden er en «rebreathing» frem til O2% er nede på 7% – ca. 5 minutter daglig i 3 dager.

http://altitudenow.com/images/Hypoxia_in_USSR.pdf

To the present day, intermittent hypoxic training (IHT) has been used extensively for altitude preacclimatization; for the treatment of a variety of clinical disorders, including chronic lung diseases, bronchial asthma, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease, emotional disorders, and radiation toxicity, in prophylaxis of certain occupational diseases; and in sports.

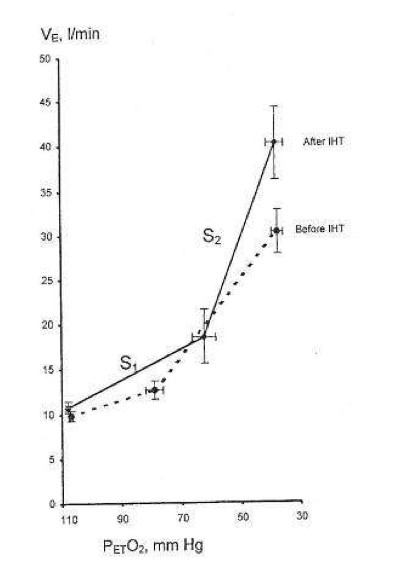

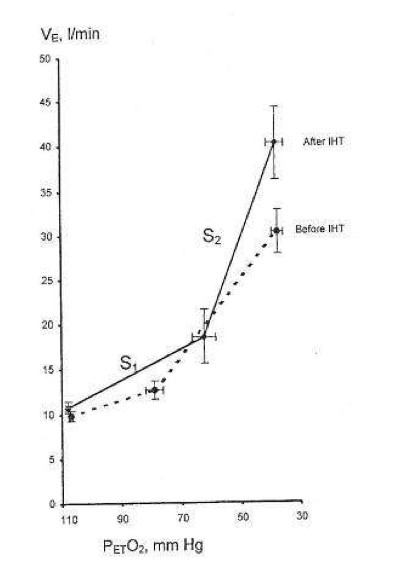

The basic mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of IHT are mainly in three areas: regulation of respiration, free-radical production, and mitochondrial respiration. It was found that IHT induces increased ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia, as well as other hypoxia-related physiological changes, such as increased hematopoiesis, alveolar ventilation and lung diffusion capacity, and alterations in the autonomic nervous system.

Due to IHT, antioxidant defense mechanisms are stimulated, cellular membranes become more stable, Ca2+ elimination from the cytoplasm is increased, and 02 transport in tissues is improved. IHT induces changes within mitochondria, involving NAD-dependent metabolism, that increase the efficiency of oxygen utilization in ATP production. These effects are mediated partly by NO-dependent reactions.

Particularly at issue are the effects in humans of such transient bouts of hypoxia when repeated many times, a practice designated as intermittent hypoxia. Furthermore, when intermittent hypoxia as a specific protocol is employed to accomplish a particular aim, for example, acclimatization to high altitude, we use the term intermittent hypoxic training or IHT.

The interested reader is referred to more extensive recent scientific and historical reviews and investigative reports in Russian and Ukrainian, particularly as related to the potential thera- peutic effects of intermittent hypoxia (Berezovsky et al., 1985; Karash et al., 1988; Meerson et al., 1989; Anokhin et al., 1992; Berezovskii and Levashov, 1992; Donenko, 1992; Ehrenburg, 1992; Fesenko and Lisyana, 1992; Vinnitskaya et al., 1992; Serebrovskaya et al., 1998a,b; Volobuev, 1998; Chizhov and Bludov, 2000; Ragozin et al., 2000). Noted also is the use of IHT in the prophylaxis of professional occupational diseases (Berezovsky et al., 1985; Karash et al., 1988; Serebrovskaia et al., 1996) and in sports (Volkov et al., 1992; Radzievskii, 1997; Kolchinskaya et al., 1998, 1999). Recent reviews from Western Europe and North America are also given (Bavis et al., 2001; Clanton and Klawitter, 2001; Fletcher, 2001; Cozal and Cozal, 2001; Mitchell et al., 2001; Neubauer, 2001; Prabhakar, 2001; Prabhakar et al., 2001; Wilber, 2001).

During successive altitude exposures, compared with the initial exposure, the higher ventilation and blood arterial oxygen saturation, together with the lower blood Pco2, implied that ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia had been increased.

In the intervening years to the present, intermittent hypoxia has been used extensively in the Soviet Union and the CIS not only for altitude pre acclimatization (Gorbachenkov et al., 1994), but also it has been proposed for treatment of a variety of clinical disorders, including chronic lung diseases and bronchial asthma in children and adults (Meerson et al., 1989; Anokhin et al., 1992; Berezovskii and Levashov, 1992; Donenko, 1992; Ehrenburg and Kordykinskaya, 1992; Fesenko and Lisyana, 1992; Redzhebova and Chizhov, 1992; Vinnitskaya et al., 1992; Lysenko et al., 1998; Serebrovskaya et al., 1998b; Chizhov and Bludov,2000; Ragozin et al.,2000, 2001), hypertension (Meerson et al., 1989; Potievskaya and Chizhov, 1992; Rezapov, 1992), emotional disorders (Gurevich et al., 1941), diabetes mellitus (Kolesnyk et al., 1999; Zakusilo et al., 2001), Parkinson’s disease (Kolesnikova and Serebrovskaya, 1998; Serebrovskaya et al., 1998a), inflammatory processes (Tkatchouk, 1994; Tsvetkova and Tkatchouk, 1999), radiation toxicity (Karash et al., 1988; Sutkovyi et al., 1995; Serebrovskaia et al., 1996; Strelkov, 1997; Strelkov and Chizhov, 1998), and certain occupational diseases (Berezovsky et al., 1985; Karash et al., 1988; Rushkevich and Lepko, 2001).

If so, then in normal humans only a few minutes of daily hypoxic exposure rapidly induces detectable increments in hypoxic ventilatory response, a hallmark of altitude acclimatization.

Hypocapnia occurs with altitude acclimatization and ventilation remains increased for days after the subjects return to sea level. By contrast, in the two above studies, eucapnia was maintained during the hypoxic exposures and neither normoxic venilation nor normoxic PC02 was altered by IHT, suggesting that only the hypoxemia and not changes in PC02 (or pH) were involved.

Changing CO2, either for the carotid body or the brain, did not induce ventilatory acclimatization to hypoxia. The work from Bisgard’s laboratory suggested that ventilatory acclimatization to hypoxia in the goat depends almost exclusively on the carotid body’s response to low oxygen. If similar mechanisms operate in humans, then ventilatory acclimatization to hypoxia, operating via the carotid body and independent of changes in pH or PCO2, can be induced by IHT. What is remarkable is that such brief periods of hypoxia can have such clearly measurable increases in the ventilatory response to hypoxia.

In addition to increasing hypoxic ventilatory sensitivity, CIS investigators have reported that IHT increases tidal volume and alveolar blood flow during exercise, improves matching of ventilation to perfusion, increases lung diffusion capacity, redistributes peripheral blood flow during exercise, decreases heart rate, increases stroke volume, and increases blood erythrocyte counts (Volkov et al., 1992; Kolchinskaya, 1993; Radzievskii 1997; Kolchinskaya et al., 1999; Maluta and Levashov, 2001). These effects have been considered to be beneficial in training athletes (Volkov et al., 1992; Radzievskii, 1997). Such findings await independent confirmation from others.

The spectral analysis suggested that after IHT there was greater parasympathetic preponderance during the hypoxic challenge than in the control group. These novel studies conducted in Ukraine suggested that IHT mimicked the usual acclimatization to high altitude, with its primarily greater parasympathetic activity (Reeves, 1993; Hughson et al., 1994). Such activation of the parasympathetic system by IHT was supported by experiments in rats (Doliba et al., 1993; Kurhalyuk et al., 2001a, b, see below).

Among these effects are that brief hypoxic stimuli of only several minutes per day for only a few days give responses that last many days, even weeks, and also that IHT apparently affects a multitude of normal functions and disease states.

This work, as well as more recent studies (Lukyanova, 1997; Sazontova et al., 1997; Kondrashova et al., 1997; Temnov et al., 1997; Lebkova et al., 1999), indicated that the basic molecular response to any type of hypoxic challenge involves the mitochondrial enzyme complexes (MchEC). There is evidence that energy metabolism under acute hypoxia is affected even before a significant decrease in oxygen consumption becomes measurable and before cytochrome c oxidase (CO) activity is significantly reduced.

In the cascade of hypoxia-induced metabolic alterations, MchEC I is most sensitive to intracellular oxygen shortage. The reversible inhibition of MchEC I leads to both the suppression of reduced equivalent flux through the NAD-dependent site of the respiratory chain and the emergency activation of compensatory metabolic pathways, primarily the succinate oxidase pathway. The switch of energy metabolism to this pathway is the most efficient energy-producing pathway available in response to a lack of O2 (Lukyanova et al., 1982).

Skulachev (1996) proposed a two-stage mechanism that allows mitochondria to regulate O2 concentrations and to protect against oxidative stress: (1) «soft» decoupling of oxidative phosphorylation for «fine-tuning» and (2) decrease of the reduction level of respiratory chain components by opening nonspecific mitochondrial inner membrane pores as a mechanism to cope with massive O2 excess.

However, parallel nonenzymatic processes result in O2 formation. This is especially the case when 02 concentrations reach the capacity of the respiratory chain enzymes. Reduction in O2 concentrations leads to an exponential decrease in radical formation. Skulachev (1995) hypothesizes that mitochondria have a mechanism for «soft» decoupling in stage 4 of the respiratory chain. This mechanism prevents the complete inhibition of respiration, the complete reduction of respiratory carriers, and the accumulation of reactive compounds such as ubisemiquinone (CoQ·-). Such a mechanism will be activated, for example, if the capacity of the respiratory chain is decreased due to a reduced availability of ADP.

In contrast to the constriction of capillaries, which prevents undesirably high O2 concentrations in tissue, «soft» decoupling allows fine-regulation on an intracellular level.

Adaptation to hypoxia by an intermittent hypoxic challenge is associated with the expression of, and a shift toward, enzyme isoforms that can efficiently function in a mitochondrial environment with high concentrations of reduced equivalents as generated during hypoxia. This prevents inactivation of the MchEC and may constitute one of the adaptation mechanisms triggered by intermittent hypoxia.

One of the most significant peculiarities of adaptation to intermittent hypoxia is free-radical processes.

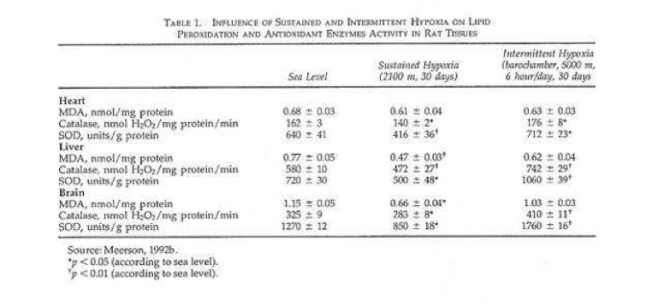

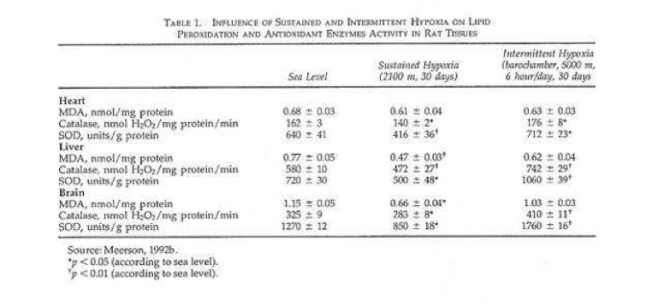

The periods of reoxygenation could lead to oxygen radical formation, which might be analogous to that occurring with normoxic reperfusion of transiently hypoxic or ischemic tissues (Belykh et al., 1992; Meerson et al., 1992a). If periods of hypoxia followed by normoxia led to formation of oxygen radicals, but if the hypoxia were much briefer than the periods of normoxia, and if the exposure sequence were repeated over days, then one might expect that antioxidant defenses could be enhanced much more effectively than in sustained hypoxia.

In a recent study rats were given shorter hypoxic exposures: 15 min five times daily for 14 d (Kurhalyuk and Serebrovskaya, 2001). When they were subsequently challenged by exposure to 7% oxygen, blood catalase and glutathione reductase activity were increased and malon dialdehyde concentration was half that of non-IHT controls. The findings were consistent with the concept that intermittent hypoxia stimulates increased antioxidant defenses.

While there was considerable individual variability in the findings (Table 2), our indexes of oxidant stress before IHT were higher in the Chernobyl workers. We used a program of IHT: isocapnic, progressive, hypoxic rebreathing lasting for 5 to 6 min until inspired air O2 reached 8% to 7%, with three sessions, separated by 5 min, of normoxia, per day for 14 consecutive days. The use of IHT was accompanied by a decrease of spontaneous and hydrogen peroxide-initiated blood chemiluminescene, as well as considerable reduction of MDA content (Table 2). Of interest, more recent study on patients with bronchial asthma, who also were characterized by indexes suggestive of oxidative stress, have shown that similar IHT produced the increase of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity by nearly 70%. This increase correlated with a decrease in MDA content (r = -0.61, P< 0.05) (Safronova et al., 1999; Serebrovskaya et al., 1999c).

Thus studies in humans and in tissues have shown that adaptation to intermittent hypoxia induces increased antioxidant defenses, acceleration of electron transport in the respiratory chain, stabilization of cellular membranes, and Ca2+ elimination from the cytoplasm. These data served as the basis for IHT in the treatment of various diseases in which free-radical production might be anticipated, for example, bronchial asthma and post-Chernobyl syndromes.

Recent studies have shown the following principal results: (1) adaptation to intermittent hypobaric hypoxia stimulates NO production in the organism; (2) excessive NO synthesized in the course of adaptation is stored in the vascular wall; (3) adaptation to hypoxia prevents both NO over-production and NO deficiency, resulting in an improvement in blood pressure; and (4) effects of intermittent hypoxia on mitochondrial respiration are mediated mainly by NO-dependent reactions (Manukhina et al., 1999, 2000a,b; Malyshev et al., 2000; Ikkert et al., 2000; Smirin et al., 2000; Kurhalyuk and Serebrovskaya, 2001; Kurhalyuk et al., 2001b; Serebrovskaya et al., 2001).

A somewhat different hypothesis has also been suggested, that the electron transport function of the myocardial respiratory chain in the NAD-cytochrome-b area is limited to a greater extent in animals poorly tolerant to hypoxia than in those that are not. In intolerant animals, even mild hypoxia leads to diminution of the oxidative capacity of the respiratory chain and of ATP production and, as a consequence, to a suppression of the energy-dependent contractile function of the myocardium. In animals more tolerant of hypoxia, this process is less manifest and develops very slowly, which confirms the lesser role of NAD-dependent oxidation of substrates in the metabolism of the myocardium of these animals (Korneev et al., 1990).

Taken together these studies suggest that IHT induces increased ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia in the absence of Pco2 or pH changes; that it induces other hypoxia-related physiological changes such as increased hematopoiesis and decreased plasma volume and increase in alveolar ventilation and lung diffusion capacity; and that it may be useful in the management of certain disease states. The effects appear to be mediated, at least in part, through release of reactive oxygen species, which then induce an increase of antioxidant defenses. In addition, IHT appears to induce changes within mitochondria, possibly involving NAD-dependent metabolism, that increase the efficiency of oxygen utilization in ATP production.

h, generally starting at 10:00

h, generally starting at 10:00

(

( ) via a hypoxia-mediated increase in their sensitivity to [H+

) via a hypoxia-mediated increase in their sensitivity to [H+ ≥ 150 mmHg) effectively silences this response (

≥ 150 mmHg) effectively silences this response (

= 150 mmHg) representing central chemoreflex response, and hypoxic (

= 150 mmHg) representing central chemoreflex response, and hypoxic ( = 50 mmHg) representing the addition of central and peripheral chemoreflexes responses. The slope of each isoxic response represents sensitivity of the chemoreflex to CO2. The inflection point at which ventilation starts to increase in response to increasing

= 50 mmHg) representing the addition of central and peripheral chemoreflexes responses. The slope of each isoxic response represents sensitivity of the chemoreflex to CO2. The inflection point at which ventilation starts to increase in response to increasing  is the ventilatory recruitment threshold (VRT), where the chemoreflex neural drive to breathe exceeds a drive threshold and starts to produce an increase in pulmonary ventilation. Ventilation below VRT represents non-chemoreflex drives to breathe and is known as the basal ventilation. The differences in ventilation between isoxic rebreathing lines at any given isocapnic

is the ventilatory recruitment threshold (VRT), where the chemoreflex neural drive to breathe exceeds a drive threshold and starts to produce an increase in pulmonary ventilation. Ventilation below VRT represents non-chemoreflex drives to breathe and is known as the basal ventilation. The differences in ventilation between isoxic rebreathing lines at any given isocapnic  can be used to calculate the hypoxic ventilatory response (indicated by vertical arrows). Note that the choice of isocapnic

can be used to calculate the hypoxic ventilatory response (indicated by vertical arrows). Note that the choice of isocapnic  affects the magnitude of the measured HVR even within the same subject (

affects the magnitude of the measured HVR even within the same subject ( values in the illustrated example. Note also that the magnitude of HVR provides little information about the characteristics of the control of breathing model, as HVR magnitude is dependent on the combination of central and peripheral chemoreflex responses.

values in the illustrated example. Note also that the magnitude of HVR provides little information about the characteristics of the control of breathing model, as HVR magnitude is dependent on the combination of central and peripheral chemoreflex responses. was required to exceed the VRT in highlanders compared to lowlanders. Since both central and peripheral chemoreceptors are actually [H+

was required to exceed the VRT in highlanders compared to lowlanders. Since both central and peripheral chemoreceptors are actually [H+ can be described as follows:

can be described as follows: where [HCO

where [HCO is 40 mmHg and [HCO

is 40 mmHg and [HCO that leads to a reduction in [H

that leads to a reduction in [H /[HCO

/[HCO of 30 mmHg rather than 40 mmHg, as at sea-level. Considering that the highlanders in our study have an adapted acid–base status (

of 30 mmHg rather than 40 mmHg, as at sea-level. Considering that the highlanders in our study have an adapted acid–base status ( relationship in highlanders compared to lowlanders, with the assumption that the chemoreceptor thresholds [H

relationship in highlanders compared to lowlanders, with the assumption that the chemoreceptor thresholds [H