Svært interessant bok om hvordan termodynamiske prinsipper ligger til grunn for alle aspekter av livet.

Cardiovascular and Respiratory Effect of Yogic Slow Breathing in the Yoga Beginner: What Is the Best Approach?

Svært spennende studie ang pustens påvirkning på vagusnerven, som bekrefter Breathing System sin Autonome pust, 5 sek inn og 5 sek ut, altså 6 pust i minuttet.

Nevner hvordan en usymmetrisk pust, f.eks. 3 inn og 7 ut, ikke påvirker vagusnerven i særlig stor grad. Og at ujjayi påvirker vagusnerven dårligere enn uanstrengt sakte pust. Ujjiayi pust har andre positivie effekter.

Nevner også at CO2 synker fra 36 til 30 mmHg når man puster 5/5 i forhold til når man ikke gjør pusteteknikk (spontan pust), men synker til 26 mmHg når man puster 15 pust i minuttet. Selv med 7s utpust synker CO2 ned til 31 mmHg. Dette er motsatt av hva studien på CO2 hos angstpasienter viser, hvor CO2 øker selv når pustefrekvensen senkes fra 15 til 12, og øker mer jo saktere pustefrekvensen er.

Nevner også noe svært interessant om at små endinger i oksygenmetning kan gi store endringer oksygentrykket pga bohr-effekt kurven som flater veldig ut ved 98% slik at en 0.5% økning i oksygenmetning kan likevel gir 30% økning i oksygentrykket.

http://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2013/743504/

The slow breathing with equal inspiration and expiration seems the best technique for improving baroreflex sensitivity in yoga-naive subjects. The effects of ujjayi seems dependent on increased intrathoracic pressure that requires greater effort than normal slow breathing.

Respiratory research documents that reduced breathing rate, hovering around 5-6 breaths per minute in the average adult, can increase vagal activation leading to reduction in sympathetic activation, increased cardiac-vagal baroreflex sensitivity (BRS), and increased parasympathetic activation all of which correlated with mental and physical health [1–4]. BRS is a measure of the heart’s capacity to efficiently alter and regulate blood pressure in accordance with the requirements of a given situation. A high degree of BRS is thus a good marker of cardiac health [5].

The slow breathing-induced increase in BRS could be due to the increased tidal volume that stimulates the Hering-Breuer reflex, an inhibitory reflex triggered by stretch receptors in the lungs that feed to the vagus [6]. In addition, the slow breathing increases the oxygen absorption that follows greater tidal volume , as a result of reduction in the effects of anatomical and physiological dead space [7, 8]. This might in turn produce another positive effect, that is, a reduction in the need of breathing. Indeed, a reduction in chemoreflex sensitivity and, via their reciprocal relationships, an increase in BRS, have been documented with slow breathing [9–13].

om hudens rolle

One key to understanding living organisms, from those that are made up of one cell to those that are made up of billions of cells, is the definition of their boundary, the separation between what is in and what is out. The structure of the organism is inside the boundary and the life of the organism is defined by the maintenance of internal states with in boundary. Singular individuality depends on the boundary.

– Antonio Demasio, The Feenling of What Happens.

Getting a grip on pain and the brain – Professor Lorimer Moseley

Nytt fantastisk informerende, opplysende og underholdende foredrag fra Lorimer Mosley om hvordan smerte egentlig fungerer.

Menneskekroppen er en organisme

Når vi snakker om menneskekroppen, behandler denne eller opplever sykdom i den, så må vi aldri miste forståelsen av at det er en ORGANISME, ikke en mekanisme. Det er så lett å sammenligne menneskekroppen med en bil, eller hjernen med en data, eller nerveysystemet med strømkabler. Men i virkeligheten er det ingen sammenheng. Kroppen, hjernen og nervesystemet er organisk, ikke mekanisk. Det er ikke en gang bio-mekanisk.

ORGANISK!!!

En organisme reparerer seg selv, bare vi gir den de riktige betingelsene. For menneskekroppen innebærer det ernæring, bevegelse, hvile, kjærlighet, livsnytelse, m.m.

Forskjellen mellom en mekanisme og en organisme er at en mekanisme består av mange enkeltdeler som er satt sammen, mens en organisme har vokst ut fra én celle. Dette innebærer at alle systemer og alle deler av en organisme påvirker hverandre, helt ned til molekylnivå. Denne videoen viser hvordan menneskekroppen vokser som en organisme.

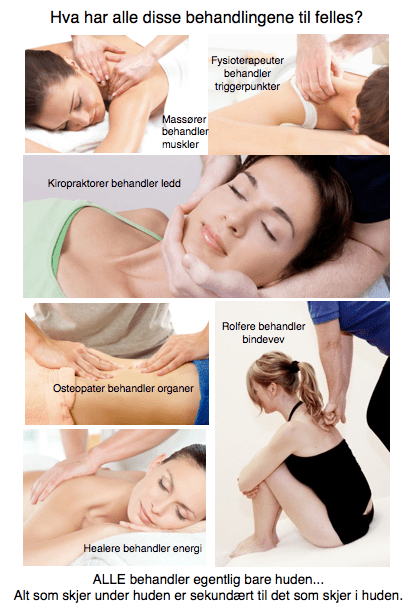

Huden – vårt største og viktigste sanseorgan

ALLE (!!!) muskel- og ledd terapeuter tar først og fremst på huden. Og ALLE gjør alt de kan for å overse det. Vi kan trygt si at huden er undervurdert i behandling av menneskekroppen. Spesielt siden ALLE behandlingseffekter egentlig er sekundæreffekter av det som skjer i hudens nervesystem og hjernens opplevelse av dette.

Huden er vårt største organ. Og vårt mest sensitive organ. Det er så tettpakket av sensoriske nervetråder at vi kan si den er «utsiden av hjernen». Vi er faktisk så godt beskyttet av huden at det er kun hjernens opplevelse av det som skjer med huden som avgjør hva som skjer med vevet under huden. Alle som tar på huden i en behandlingssituasjon er fullstendig underlagt nervesystemets reaksjon på berøringen.

Muskler, ledd og bindevev gjør bare det nervesystemet befaler. Når vi vet hvilken direkte kobling huden har til nervesystemet og hjernen kan vi også rette behandlingskonseptene våre direkte på det som faktisk gir behandlingseffekt: Nervesystemet

Når vi trykker på et triggerpunkt, et ømt område av en muskel, så finnes det svært få trykksensitive nerver i selve muskelen. De finnes hovedsaklig i huden og vevet rett under huden. Smerten vi opplever av trykket kommer altså ikke av at vi trykker på muskelen, men at vi trykker på huden. Selv om det kjennes ut som at vi trykker hardt og dypt inn vevet, så er det hudens nerver som reagerer på trykket. Om vi bedøver hudens nerver når vi f.eks. er støle, så forsvinner trykksensitiviteten også. Når vi jobber med å dempe smerte trenger vi altså ikke trykke hardt inn i muskelen, vi trenger bare å ha en litt smartere tilnærming til huden.

Smerte er en subjektiv opplevelse som er ment å beskytte kroppen. Det innebærer et tett samarbeid mellom hjernens registrering av faresignaler fra huden og dens interne kart over kroppen. Fra et evolusjonært perspektiv er det større farer i omgivelsene enn internt i kroppen. Derfor dekker de fare-registrerende nervene (nociceptorer) hele kroppens overflate. Det er også noe av grunnen til at vi føler oss trygge og slapper bedre av når noen tar på huden vår på en behagelig og ikke-truende måte.

Det krever en ganske stor omveltning for å innse hudens rolle i smertebehandling. Det er veldig mye som vi tidligere har tatt for gitt som må snus på hodet. Vi må lære oss å legge merke til noe medisinsk vitenskap har brukt 200 år på å overse.

Med en helt ny forståelse av menneskekroppen og behandling av nervesystemet kan vi også behandle smertetilstander direkte, men uten å gi ny smerte slik de «gamle» behandlingsformene gjør. De som overser huden, vårt største og viktigste sanseorgan, og (håpløst) prøver å trykke fingrene igjennom den.

Med den nye behandlingsformen DermoNeuroModulation snur vi alt på hodet og behandler smerte UTEN å gi ny smerte. Når vi vet hvordan huden og nervesystemet fungerer trenger vi kun å gi en behagelig og interaktiv behandling av huden, og smerte dempes umiddelbart.

Neurosensory mechanotransduction through acid-sensing ion channels.

Veldig interessant studie som nevner at pH-sanse nerveceller(ASIC) finnes i Merkel og Ruffini celler i huden, og at i ASIC knockout mus så reagerer de ikke på trykk.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23490035

The ASIC proteins are involved in neurosensory mechanotransduction in mammals. The ASIC isoforms are expressed in Merkel cell-neurite complexes, periodontal Ruffini endings and specialized nerve terminals of skin and muscle spindles, so they might participate in mechanosensation.

In knockout mouse models, lacking an ASIC isoform produces defects in neurosensory mechanotransduction of tissue such as skin, stomach, colon, aortic arch, venoatrial junction and cochlea. The ASICs are thus implicated in touch, pain, digestive function, baroreception, blood volume control and hearing.

The Pathogenesis of Muscle Pain

Viktig studie fra S.Mense som nevner mange aspekter av muskelsmerter, som trykksensitivitet, sentral sensitering og referert smerte.

http://www.cfids-cab.org/cfs-inform/Neuroendocrin/mense03.pdf

The typical muscle nociceptor responds to noxious local pressure and injections of BKN; however, in animal experiments, receptors also can be found that are activated by one type of noxious stimulation (mechanical or chemical) only. This finding indicates that different types of nociceptors are present in skeletal muscle, similar to the skin in which mechano-, mechano-heat-, and poly-modal nociceptors have been reported to exist [12••].

The sensitization is associated with a decrease in the mechanical threshold of the receptor so that it responds to weak pressure stimuli. The sensitized muscle receptor still is connected to nociceptive central nervous neurons and thus elicits subjective pain when weak mechanical stimuli act on the muscle. This sensitization of muscle nociceptors is the best established peripheral mechanism explaining local tenderness and pain on movement of a pathologically altered muscle.

Of these neuropeptides, SP is of particular interest because, in experiments on fibers from the skin, SP has been shown to be predominantly present in nociceptive fibers [26]. The peptides are released during excitation of the ending and influence the chemical milieu of the tissue around the receptor. This means that a nociceptor is not a passive sensor for tissue-threatening stimuli, but actively changes the micromilieu in its vicinity by releasing neuropeptides. SP has a strong vasodilating and permeability increasing action on small blood vessels.

Mechanism of referral of muscle pain

The expansion of the input region of the inflamed GS muscle nerve likely underlies the spread and referral that is common in patients with muscle pain. The mechanisms mentioned previously can explain referral as follows: when a muscle is damaged, the patient will perceive local pain at the site of the lesion. If the nociceptive input from the muscle is strong or long-lasting, central sensitization in the dorsal horn neurons is induced, which opens silent synapses and leads to an expansion of the target area of that muscle in the spinal cord (or brain stem). As soon as the expansion reaches sensory neurons that supply peripheral areas other than the damaged muscle, the patient will feel pain in that area outside the initial pain site. In the area of pain referral, no nociceptor is active and the tissue is normal. The referral is simply caused by the excitation induced by the original pain source, which spreads in the central nervous system and excites neurons that supply the body region in which the referred pain is felt. This way, a trigger point in the temporalis muscle can induce pain in the teeth of the maxilla when the trigger point-induced central excitation spreads to sensory neurons that supply the teeth [43•].

to studier på hvordan huden reagerer på trykkømhet

To studier på hvordan huden påvirker trykksensitivitet.

Ene nevner at trykkømhet i fibromyalgi er værst over der en nerve er, ikke så mye over knokler eller muskler. Nevner at en bedøvende krem på huden ikke endrer trykkømhet.

Andre nevner at trykkømhet normalt faktisk blir mindre av en bedøvende krem, og bekrefter at ømheten er større over en nervebane enn over knokkel eller muskel.

Increased pressure pain sensibility in fibromyalgia patients is located deep to the skin but not restricted to muscle tissue

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0304395996000127

The site with underlying nerve had a lower PPT than the bony site (P > 0.001) and the ‘pure’ muscle site (P > 0.001), respectively. These relations remained unaltered by skin hypoesthesia.

Application of EMLA, compared to control cream, did not change PPTs over any area examined. The results demonstrated that pressure-induced pain sensibility in FM patients is not most pronounced in muscle tissue and does not depend on increased skin sensibility.

Pressure pain thresholds in different tissues in one body region. The influence of skin sensitivity in pressure algometry.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/10380724

The PPT was significantly (p < 0.001) lower at the «muscle/nerve» site than at the bony and «pure» muscle sites.

However, PPTs after control cream were lower (p < 0.001) over all examined areas than those obtained prior to cream application. Thus, EMLA cream increased PPTs compared to control sites in all examined areas (p < 0.001). Under the given circumstances, skin pressure pain sensitivity was demonstrated to influence the PPT.

Painful and non-painful pressure sensations from human skeletal muscle

Viktig studie om hvordan huden påvirker trykksensitivitet i muskler. Nevner at trykksensitiviteten sitter mest under huden i dyperliggende vev.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15480607

In studies attempting to block the skin contribution of the pressure pain sensitivity, a thoughrough assessment of cutaneous anaestesia is either not included or only a partial loss of skin sensitivity is reported. Thus, it is likely that the cutaneous mechanoreception was partly intact, which might affect the pressure sensitivity of deep tissue.

With the skin completely anaesthetised to brush and von Frey hair pinprick stimulation, skin indentation with the strongest von Frey hair caused a sensation described as a deep touch sensation.

The present data show a marginal contribution of cutaneous afferents to the pressure pain sensation that, however, is relatively more dependent on contributions from deep tissue group III and IV afferents. Moreover, a pressure sensation can be elicited from deep tissue probably mediated by group III and IV afferents involving low-threshold mechanoreceptors.